Spontaneity in Stained Glass Work

| Spontaneity in Stained Glass Work |

| Robert Oddy |

Stained glass does not lend itself to spontaneity. We design, thinking always about how the glass will be cut and what glass will be available to us. Then, the fabrication is a very slow and meticulous process, requiring accuracy of cutting so that the pieces fit together closely – glass doesn’t bend, stretch or squash. We have to do too much careful planning, and too much engineering! How can we make our subjects come alive, with movement and energy, when we cannot use our bodies to express these things while we are doing the art?

|

| Figure 1: Design sketch for |

| Maureen’s Garden (1989) |

A painter can quite literally put various expressions of energy into his or her brushstrokes. I certainly would not advocate a physically flamboyant style in a stained glass studio, for obvious safety reasons! I am thinking more of taking some of the detailed planning out of the early stages of the project, and spreading the decision-making out through all stages of the work. I am largely self-taught, both in stained glass work and in art generally.

I have learned a lot, serendipitously, by talking with and watching other people. But, I developed my own ways of doing things. And my methods do allow for more spontaneity than most that I have observed.

|

| Figure 2: Cartoon for Maureen’s Garden |

| one sixth of the window, bottom right |

When I design, I don’t consciously think of practical matters of fabrication. I do think of the effects of light and value that I can achieve with the glass. Figure 1 shows the original sketch of Maureen’s Garden (1989). It’s really a conceptual sketch. Little detail is apparent, and the colors are very simply represented. It was enough to discuss the project with the client, because they understood and trusted that my choice of glass would create variety and vivacity. And for my part, I trust that I will be able to figure out a way of implementing the image that I hold in my head when I build the window. In this case, my client (the husband) was an architect, and suggested that I reverse the design to take advantage of the available lighting. During my first decade as a stained glass artist, my sketches were very rough, and even the full size cartoon was not complete in every detail. I would leave some of the detail to be worked out during fabrication. Figure 2 is a photo of the full size drawing of the lower right hand section of the window. Note that this corresponds to the lower left in the sketch because the design was reversed. The drawing is a terrible mess because the panel was built on this drawing and it acquired many stains: blood, sweat and tears as well as flux, burns and patina. So, some of the detail is hard to make out. Compare this with Figure 3.

|

| Figure 3: Detail of Maureen’s Garden |

| complete bottom right section |

You can see some major shapes and lines drawn in, but there is virtually no detail of any of the flowers. A few lines indicate where the stems will be, and the shape of the ghostly rose. I built the flowers individually. Some, such as the lilies at the bottom, were drawn on separate pieces of paper; others were not drawn at all. Then I arranged the flowers on the cartoon (if I may use that word for this scruffy drawing!), and planned the foliage to surround them. That is when I added some of the darker leaf shapes that you can see in the drawing. If you compare Figures 1 and 3, you will see that the original sketch was only used as a rough guide.

Later, I began to use Photoshop software to help with design and drawing, and my drawings became more complete.

|

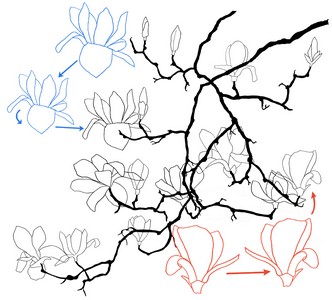

| Figure 4: Photoshop file with edits |

As my business grew, I found that some clients (not all) wanted more detail in the sketch before approving it. So, I had to shift some of the spontaneity into other parts of the process. Photoshop added new opportunities for spontaneity: I found that I could play during the design stage. It is so easy to edit a drawing on the computer that I could move any part of the drawing around, switch alternative features in and out, resize and reorientate individual features. In Figure 4, I am adding two magnolia blossoms (shown in red and blue) to a design. I tried rotating the blue blossom, and I flipped the red one over. The original outlines of these blossoms are a little too large, so I have scaled them down.

A few years ago, I began to publish patterns for relatively small projects that illustrated aspects of the techniques I use in my commissioned artwork, and it was interesting how different the process was from my usual way of working. I had to design the piece completely, draw it neatly, specify the glass and annotate the drawing with letters representing the glass to be used in each place in the design. This was so that I could take photos of the work in progress for the magazine article, and to make sure that the pattern would work out well for a reader who wished to make the piece.

There are many factors that contribute to artistry in stained glass. For me, perhaps the most important one is the choice of glass. Not just the choice of which type of glass to use, but which part of the sheet for each piece in the window.

|

| Figure 5: Hybrid Tea Rose, 2007 |

We have a wealth of types of glass – multi-colored opalescents, streakies and whispies, ripples, granite, all in many variations and combinations. We can use these to give impressions of subtleties, such as shadows and soft graininess, which lead lines cannot capture but which a painter can. In Figure 5 you can see a small panel depicting roses. All the glass in the blossoms comes from the same sheet, but I have chosen the pieces with a view to distinguishing between light areas, illuminated by the sun, and parts in deep shade. Also, I have used the streaks in the glass to suggest the curvature of the petals. I need to be able to make these choices while I am building the window. Sometimes, I will make small alterations to the design in order to exploit a particular piece of glass.

|

| Figure 6: Hybrid Tea Rose, in progress |

I do a lot of natural subjects – floral, trees, animals. The panels grow a little like the subjects themselves, but not quite in the same order. I usually make main features, such as blossoms, first, then I add the stems and the leaves (Figure 6). Flowers and leaves are not precise geometric shapes, so it is more important that the glass is used creatively than that the shapes match the original pattern exactly. And my petals and leaves tend to be quite complicated shapes because I feel that simplifying the lines too much makes them look flat and lifeless. I assemble the features, soldering them together as I go along, and hold them up to the light frequently to make sure that I am getting the effect I want.

Color saturation and value are two different things, and both can be quite different when the glass is on the bench as opposed to transmitting light. Color depends on the chemicals in the glass, and may appear different in reflected light than in transmitted light. Value (the darkness-lightness scale ) depends on the opacity of the glass, which is only fully apparent in transmitted light.

In future articles, I will focus on specific techniques that I use, but first I wanted to explain my approach, and how I increase the enjoyment of the whole creative process. I am not at all interested in telling you how stained glass should be done. After all, that would be to discourage your artistic spontaneity!

web: www.robertoddy.com | mail: [email protected] | phone: (315) 200-2260