The Anatomy of a Commission

| The Anatomy of a Commission |

| Could a Rose, by Any Other Technique, Look So Sweet? |

| Robert Oddy |

This is the text of an article that appeared in the magazine Glass Craftsman, Issue No. 158, Feb/Mar 2000

Technique is the servant of the artist, not the master. Yet we are forced to focus on it occasionally, because art and technique are intertwined. Each technique produces a distinctive range of effects, and imposes some limitations. Artists choose among techniques for different reasons. Sometimes we opt to stay with well-known techniques and explore their potential. Other times, we start with a desired effect—an image in the mind—and invent techniques that can produce it, often adapting existing methods. Artistic considerations are often compromised by engineering ones, in glass arts more than most. A stained glass window is a heavy, fragile structure, so we must know the limitations of the materials and use ingenuity to build something that is as robust as possible. Scale is an important factor here: what works in a small window may have to be implemented quite differently for a larger scale.

|

| Fig 1. Roses, 1999. Left-hand panel, 12″ wide. |

| Detail: Bourbon rose |

The major theme in my work is the ‘realistic’ representation of natural subjects, such as plants and animals; trying to capture the depth, subtlety and complexity inherent in the natural world. For the most part, I use techniques based on the copper foil method of building windows, and obtain glass from many of the marvelous manufacturers operating today. In this article, I will try to show you how I use, adapt, and perhaps abuse these techniques to achieve what I want. I will use one recent project as a means of demonstrating my own creative process. Figure 1 shows a small part of the work, which I will use as an illustration. There is not space here to cover all my techniques, or even to go into much detail, and I am assuming that you already have some knowledge of basic stained glass and copper foil methods.

Origin of the project

The project I shall describe here was a wonderful opportunity to indulge my penchant for horticultural themes. The commission was for a pair of 63″ x 12″ side-lights bordering the main entry door to a private residence. In this case, my client, a knowledgeable amateur rose grower, had a specific theme in mind for the windows: a depiction of several of his favorite varieties of rose. He also suggested incorporating the historical development of the rose. He was not asking for scientific illustration, although his preference was for realism in the imagery.

Designing

|

| Fig 2. Design sketch |

| – left-hand panel |

The long narrow shape of the windows, together with the notion of a recognizable sequence led to the decision to give each rose variety an essentially separate space within the design. So, the left hand panel contains a column of earlier roses, starting with the ancient wild (“Species”) rose at the bottom, and including some old garden roses (pre-19th century). The right hand panel contains modern cultivated roses: shrub, floribunda, grandiflora, hybrid tea and miniature. I went back to my studio laden with a small library of books and magazines about roses! The challenge was to represent the roses accurately enough that the varieties would be recognizable to an expert. I found several distinguishing characteristics. Obviously blooms and buds differ in form and number of petals. Leaves also vary in size and color, as do stems and thorns: some roses have widely spaced large thorns, others have a mass of tiny thorns, almost making the stems appear fuzzy. The overall form of the plant, such as height and bud clusters, is also a distinctive feature of each variety. I did my research and prepared a color pencil sketch for the client’s approval (figure 2 shows one of the proposed panels). I pay very little attention to implementation concerns at this stage—I decide what I want to do, and figure out how to do it later.

Fabrication – Overview

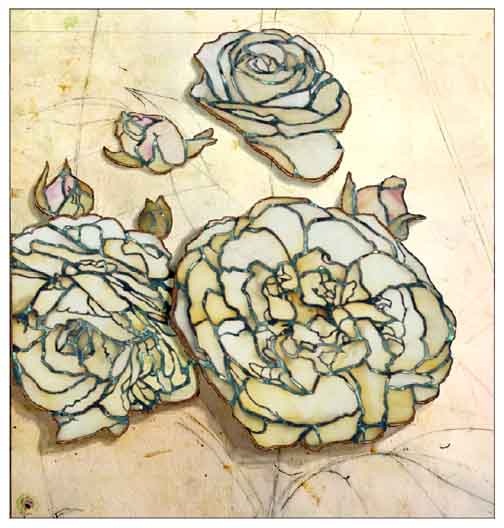

|

| Fig 3. A Rose blossom showing the cut lines |

For a window of this complexity, with a natural subject (as opposed to geometric or stylized designs), I do not draw a detailed cartoon. I work on a large sheet of stretch-paper—a “work sheet”—on which I begin by drawing the outline of the window and then sketching important lines (e.g. plant stems) and rough indications of the major features (blossoms and leaf clusters). I focus on one section of the window at a time, beginning with major features, joining up and filling in spaces until the section is complete. So, detail aspects of the design process continue throughout the fabrication process. When all the sections of a panel are complete, I assemble them and add any structural reinforcement within a specially constructed wooden frame, which will serve to support the window while I manipulate it on the bench and during storage prior to installation.

Fabrication – Details

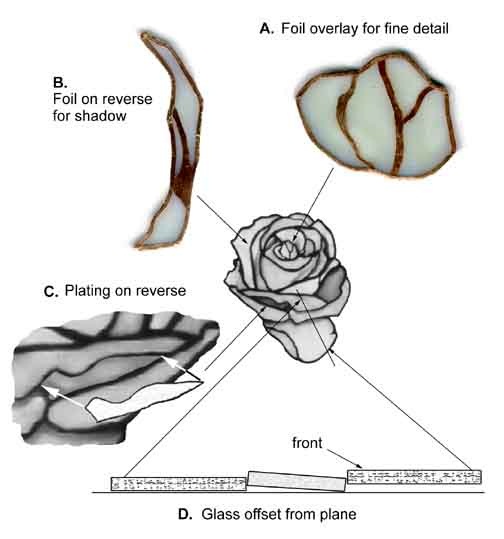

|

| Fig 4. Detail techniques |

What I mean by a ‘section’ will vary from one design to another. In the project we are looking at here, each type of rose occupies a convenient section. Let’s use the Bourbon rose as an example (Figure 1). I draw each blossom and bud on a separate piece of paper, and decide which lines will be cut lines, i.e. places where separate pieces of glass will meet (Figure 3). In traditional leaded glass work, realism is seriously compromised in the treatment of lines. When we view an object in the real world, we see its edges as infinitesimally thin lines; actually more as transitions between color values. In work such as these rose panels, I choose to try to minimize the compromise without abandoning the tradition of leaded glass entirely (as with the extensive use of paint or fusing, for instance). Using copper foil, I can make the lines quite thin and also add subtlety by varying the thickness of the lines. Also, to get fine detail, when adjacent pieces are very small and of the same color, I will use a copper foil overlay instead of cutting separate pieces of glass (see figure 4-A). This is easier (I already have more than enough intricate cutting to do!) and the lines can be very fine. But note that a long thin copper foil line on the surface of the glass is fragile. I might use copper or brass wire for reinforcement under the foil if I am concerned about this.

|

| Fig 5. Use of glass texture to suggest depth |

Before cutting the glass, I make a photocopy of the blossom. One copy is cut up into templates used to mark the glass for cutting. The other is used as a guide to lay out the glass in the correct positions for soldering. I use several techniques to achieve a lively and 3-dimensional impression. Shading can be done by careful choice of glass (color saturation, opacity), or by applying copper foil to the reverse of the glass (figure 4-B), or by plating with a second layer of glass (figure 4-C). Dense glass will diffuse the shape of whatever is attached to the reverse. A feature (such as a petal or leaf) can be made to stand out visually by offsetting the glass a little, behind the plane of the surrounding pieces (figure 4-D). The streaks or grain within the art glass can be used to suggest the curved surface of a petal or leaf (figure 5). I work with a glass palette readily at hand. I keep most of my scrap glass (anything more than about 2 square inches, if it’s nice art glass). While I am working on a particular section of a window, I pull out anything from stock that might be useful, and arrange it around the bench. (One reason for dividing the work into sections is to limit the bench area needed for the palette!) Sometimes I can find the variations I am looking for within a single type of glass. Other times I need to draw from several different types. Copper foil overlays are applied first to the cleaned glass, then each blossom is fully assembled—edges foiled and soldered.

|

| Fig 6. Bourbon blossoms and buds laid |

| on the work sheet for fitting and joining |

The next step is to arrange the completed blossoms and buds on the work sheet. At this point I may change my mind about the positions that I originally sketched. Some of the features will overlap each other. In such cases, I use the foreground blossom to mark the other one, and cut away some of the latter assembly to fit (figure 6). The new cut will have to be re-foiled, of course, then the components can be joined. Now marks can be made on the work sheet indicating the exact final positions of the assembled features.

|

| Fig 7. Leaf veins engraved on reverse |

To make foliage, I draw a collection of leaf shapes freehand directly onto glass, and cut them all out. Sometimes a leaf may be made of more than one piece of glass (if it is folded, for instance). If I want veins to be visible on the leaves, I usually engrave them on the reverse side of the glass: this gives a subtle effect, although it can be far too subtle if the glass is very dense! (Figure 7). So, now I have a large assortment of leaves to arrange on the work sheet around and between the blossoms and buds. Some of them will need trimming, and where a leaf lies in front of a blossom, the blossom will need to be cut again. Pieces that can be joined are foiled and soldered as I go along. The thorns on the stems in this piece are made with copper foil overlays carved with a craft knife before soldering (figure 8). The background is filled in as the shapes are determined by the already assembled pieces—quite literally: I trace around the edges of the completed parts directly onto the background glass.

|

| Fig 8. Two kinds of thorns |

| Made by carving copper foil |

Some pieces are difficult shapes to cut. In those instances I use a ring saw. I stick white gummed labels onto the glass, mark it with a very fine pen for accurate cutting. If you mark the glass directly, the coolant in the saw tends to wash it off while you’re cutting.

I frequently check the effect that I am achieving by standing the work in a studio window. I view it from close up and also at some distance.

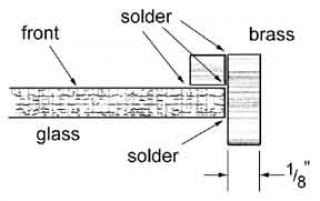

|

| Fig 9. Brass frame: cross-section |

If a large panel requires structural reinforcement, I usually use 3/8″ x 1/8″ or 1/8″ x 1/8″ brass bar across the panel, bent to follow a line in the design and attached to the reverse, so that it will not be visible from the front. The windows I have been describing here do not need interior reinforcement—they are only 12 inches wide. These panels are framed on all four sides with two brass bars arranged in an L shape, which provide adequate support (figure 9). In the client’s home, they were installed in a deep rabbet and secured with oak stops.

The completed windows are shown in figure 10, photographed prior to installation.

web: www.robertoddy.com | mail: artist@RobertOddy.com | phone: (315) 200-2260